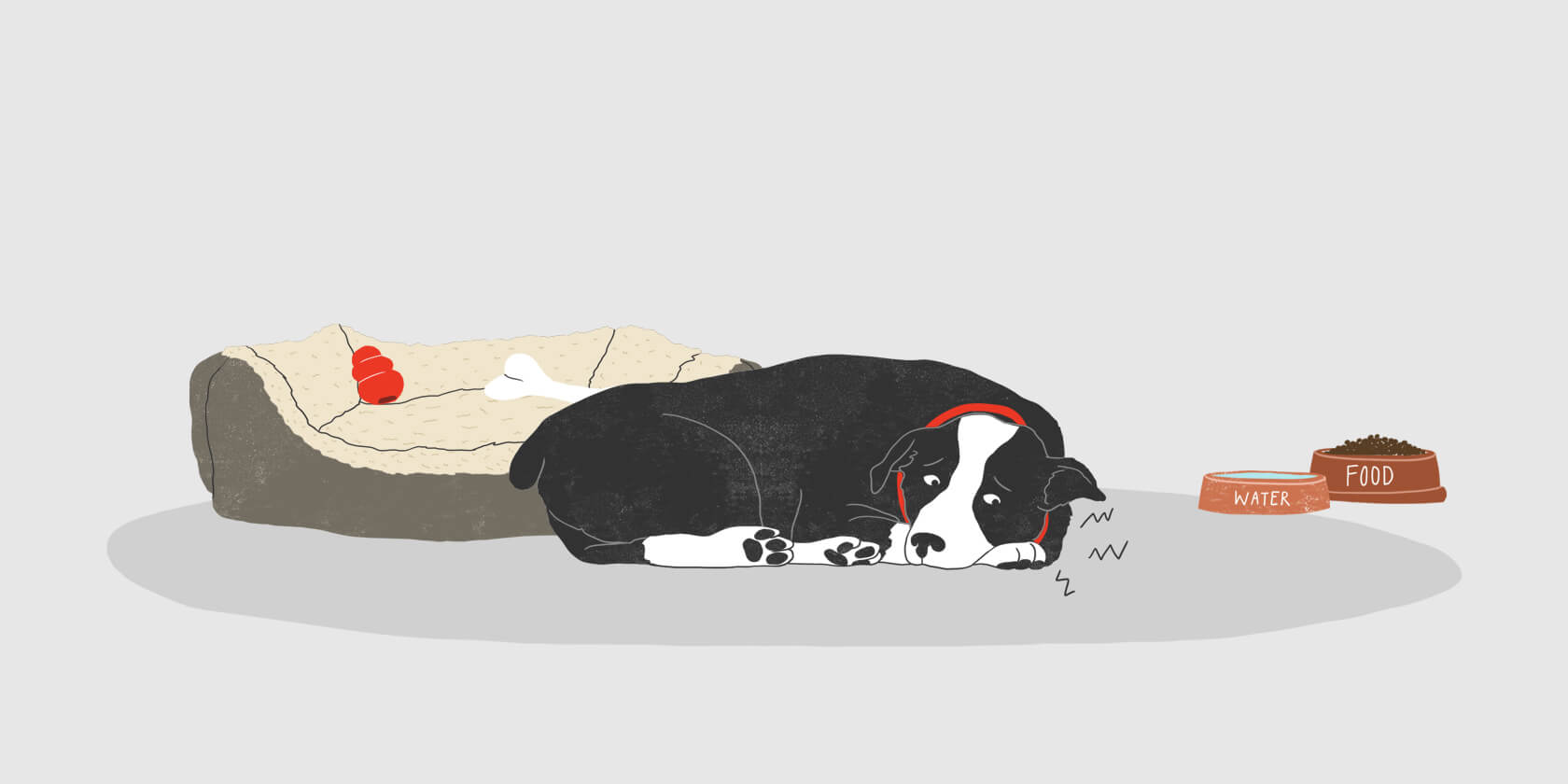

Pain can be a tricky thing to identify in your dog. Pet owners often think of their dog’s pain as their inability to move or activity level – lower activity levels may equate to more pain. Although true, pain may be present in many other forms other than movement, like behavior. Dogs tend to hide their pain, often showing only subtle physical and behavioral signs. This makes it difficult for you to notice they’re suffering and potentially prolonging their discomfort.

There are two primary types of pain in dogs— acute and chronic. Here is some more information on each.

Acute Pain in Dogs

Acute pain is pain that has just come on or has only been present for a short amount of time. It’s typically associated with an illness, injury, or surgery, and helps the brain signal that an area should be protected to allow for healing.

Acute pain typically causes behavior changes, such as not wanting to be touched, hiding, or keeping weight off an injured paw. These behaviors are protective in that they restrict use of the affected area and allow the injury to heal. Acute pain can also be known as adaptive pain because it’s normal pain that resolves once the injury heals. A cut to the paw is an example of adaptive/acute pain. If the pain is not addressed, or the wound is untreated, this can get worse and transition to chronic pain. The beginning of joint damage is another example of adaptive pain and will transition to chronic pain if left untreated.[1]

Chronic Pain in Dogs

Chronic pain can cause severe stress to your dog and greatly decrease the joy they get out of life. This is often called “maladaptive pain” because it doesn’t appear to have any sort of protective purpose. Arthritis is a good example of maladaptive pain because it’s not a disease that can be cured—the injury and inflammation are always present. This leads to a constant bombardment of the brain with pain signals, and without recognition and proper management, the pain can take on a life of its own. Without recognition and proper management, chronic pain can progress, firing painful signals to the brain even in different parts of the body and when no pain-inciting stimulus is present[1].

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common cause of chronic pain in dogs (and not just older dogs). It’s estimated to occur in nearly 40% of all dogs[2]. Hereditary and other congenital factors can cause OA in even very young dogs, and it can develop following a severe injury to a joint[3]. OA can occur in dogs of all different breeds and mixes, and of all different sizes and ages[4].

Signs that can indicate osteoarthritis pain in dogs include:

- Limping

- Less willing to jump up or down

- Less willing to climb stairs

- Less active or “slowing down”

- Stiffness

- Slower getting up after sleep or a nap

Treatment of Acute Pain

Depending on its severity and cause, acute pain is often treated with a combination of veterinarian-prescribed pain medications and rest. Acute pain typically only lasts for a short period of time unless it’s associated with the onset of OA or the cause of the pain is not determined and treated – at which point it can become chronic pain.

Treatment of Chronic Pain

Chronic pain associated with OA is not curable, but it can be managed. With proper medication, the pain signals that travel to the brain are reduced, giving the nervous system a chance to recover. This helps to keep your dog comfortable, reduce their stress[5], and allows them to engage in activities they love like playing fetch, being pet, and going on walks with you.

If your dog is showing signs of pain, take note of them and continue to monitor and evaluate if their pain signs are returning and be sure to talk to your veterinarian. Your veterinarian can help you determine the cause of your dog’s pain and get them on a proper pain management plan — giving them their quality of life back.

ZPC-00327R2

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: Librela is for use in dogs only. Women who are pregnant, trying to conceive or breastfeeding should take extreme care to avoid self-injection. Hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, could potentially occur with self-injection. Librela should not be used in breeding, pregnant, or lactating dogs. Librela should not be administered to dogs with known hypersensitivity to bedinvetmab. Adverse events reported post-approval include ataxia (lack of balance/coordination), anorexia (loss of appetite), lethargy (tiredness), emesis (vomiting), and polydipsia (increased drinking). The most common adverse events reported in a clinical study were urinary tract infections, bacterial skin infections and dermatitis (skin irritation/inflammation). See full Prescribing Information.

See the Client Information Sheet for more information about Librela.

- The Experience of Chronic Pain 2019 Proceedings. Zoetis Petcare. (2019).

- Wright, A, et al. ISPOR Abstract. Diagnosis and Treatment Rates of Osteoarthritis in Dogs Using a Health Risk Assessment (HRA) or Questionnaire for Osteoarthritis for General Veterinary Practice. (2019).

- Henrotin Y, Sanchez C, Balligand M. (2005). Pharmaceutical and nutraceutical management of canine osteoarthritis: Present and future perspectives. The Veterinary Journal. 170:113–123.

- Rychel J. (2010). Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Topics in Companion Animal Medicine. 25(1):20–25.

- Gaynor JS, Muir WM. Handbook of Veterinary Pain Management. Mosby. St louis, MO. 46-52.